Developments on the Inkblot Test: Scoring

After Hermann Rorschach’s sudden death in 1922, his inkblot test began to take on a life of its own as it traveled around the world.

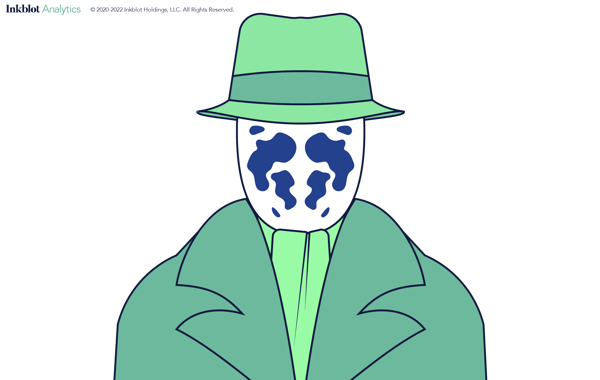

The Rorschach is a timeless symbol of psychology. The way it works is deceptively simple.

The Rorschach is a timeless symbol of psychology. The way it works is deceptively simple. With a paper medium, ink, and basic principles of symmetry, personality can be rendered through the protocols of an experiment in perception. Perception is the place where the mind meets the world; it is the bridge between the subjective and the objective. The origins of the inkblot test are an equal blend of the arts and sciences. And although Rorschach’s test is the most widely known, he was not the first artist or psychologist to use the unmistakable inkblots.

Circa 16th Century—The story of Rorschach’s inkblots began somewhere in Leonardo da Vinci’s divine collection of notebooks, where he wrote on the process of stimulating and arousing the painter’s mind, professing that “if you look at any walls with various stains or with a mixture of different kinds of stones, if you are about to invent some scene you will be able to see in it a resemblance to various different landscapes adorned with mountains, rivers, rocks, trees, plains, wide valleys, and various groups of hills. You will also be able to see divers combats and figures in quick movement, and strange expressions of faces, and outlandish costumes, and an infinite number of which you can then reduce into separate and well conceived forms. With such walls and blends of different stones it comes about as it does with the sound of bells, in whose clanging you may discover every name and word that you can imagine,” (Da Vinci, 1908, p. 173). Many artists and philosophers today argue that da Vinci’s note described the essence of pareidolia, the visual function of apophenia, a phenomenon where humans perceive meaningful patterns in otherwise ambiguous stimuli. More intriguing is his reference to the perception of movement in accidental forms, a concept that would underlie the foundation of Hermann Rorschach’s inkblot experiment.

1857—Written in the middle of the century, Justinus Kerner gathered and organized his collection of inkblots into the book Kleksographien, though the book itself would be published posthumously in the year 1890. Kerner was a doctor and a poet who dropped ink into a piece of paper, folded then unfolded it, and wrote poetic reactions to the art. The blotograms became a popular game known commonly as Blotto or klexography.

1884—Hermann Rorschach was born in Switzerland on November 8th. He was a Scorpio, an astrological sign that many other famous painters share: Pablo Picasso, Claude Monet, and Georgia O’Keefe. It is only fitting that Rorschach would become a man of art and intellect.

1895—Alfred Binet, who is known for creating the world’s first intelligence (IQ) test, and his colleague Victor Henri published a book that focused on the individual differences of psychological characteristics, particularly the higher level processes of cognition. The two, inspired by da Vinci, proposed that inkblots could be used to test an individual’s visual imagination. In specific, the two wrote, “Consider an ink stain with a strange outline on a white paper; for some this stimulus does not appeal to them; for others who have a quick visual imagination (Leonardo da Vinci for example) the small ink stain appears full of figures, which we will note the species and the number,” (Nicolas et al., 2014, p. 120, Binet and Henri, 1895).

1897, 1898—Harvard psychologist George Dearborn published two papers on inkblots. The first, titled Blots of ink in experimental psychology, described a technique for constructing inkblots as well as the advantages of “chance characters'' for experimental usage, which ranged from the contents of consciousness, to memory, to imagination, to association (Dearborn, 1897, p. 391). Dearborn’s process was quite simple: place small drops of ink into the center of a piece of paper, fold it, and then compress with the fingers. The blots were not entirely symmetrical or of great depth in character: they were simply inkblots. The following year Dearborn published the results of an experiment with inkblots titled A study of imaginations. Subjects were tasked with flipping over an inkblot from a deck of ten cards, then without moving the card, they tapped the desk once a whole image appeared to them in the inkblot. The experimenter would record the time for each response, as indicated by the tap, and the object seen (i.e. the percept). The procedure was repeated for twelve sets of decks, for a total of one hundred and twenty cards.

1899—Psychologist Stella Emily Sharp published the results from a series of psychological tests which featured an experiment with inkblots. This method of blots was inspired by Binet and Henri’s 1895 book, which Sharp’s article was titled under the same name, as well as Dearborn’s procedure for constructing inkblots. Sharp used ten cards in a series and probed the participants to name the objects seen, in whole or in any small details of the inkblot over the course of five minutes. Subjects were allowed to rotate the cards at will. Sharp noticed the variations, or individual differences, of each subject’s associations with a given inkblot. She wrote, “a particular blot may call up in the mind of a subject, through association, a number of objects similar to this in form, and he enumerates the objects one after another; while to another individual the same blot seems filled with pictures representing some action or situation, which are reported, often with touches of fancy or sentiment,” (Sharp, 1899, p. 372). Although she was studying imagination, the seeds of Rorschach’s functions of perception and apperception were planted in the history of the inkblot.

1900—Child psychologist E.A. Kirkpatrick published the result of an experiment with inkblots titled, Individual tests of school children. One test included the use of inkblots, where school children were instructed to name the objects seen in a series of four inkblots, each displayed for one minute. Kirkpatrick concluded that younger children were more imaginative in terms of seeing objects in the inkblots.

1908—Eugen Bleuler, who was Rorschach’s doctoral advisor, coined the term schizophrenia. This is an important development as Rorschach would eventually note that his schizophrenic patients had unique but related responses to the Blotto game, eventually leading to the development of his inkblot technique.

1910—Guy Whipple published the first standardized set of twenty inkblots in his book, Manual of mental and physical tests. This review hinted at the potential active associative mental activity behind the inkblot task with regards to the study of imagination. The standardized set of inkblots was not printed, but was made available for purchase from the publishing company located in Chicago, Illinois.

1911—Rorschach attempted his first experiment with inkblots in collaboration with friend Konrad Gehring, a school teacher in Münsterlingen. The experiments were inspired by curiosity rather than grand design, however the two investigated the production and implementation of inkblots with regards to imagination. During this time Rorschach was interested in the artistic productions of his schizophrenic patients with other mediums like clay and paint.

1915—Volume number two of Manual of mental and physical tests was published by Whipple. The author highlighted the work of W.H. Pyle, who is credited with the modification of Dearborn’s method for the purposes of group testing. Whipple noted that the major findings were generally related to reaction times, age differences, occupation, race, and classification of response types.

1916—F.C. Bartlett published a manuscript titled, An experimental study of some problems of perceiving and imaging. Bartlett developed his own set of thirty-six inkblots for experimentation, a few of which closely resemble what would become Rorschach’s style (see cards six and ten). Importantly, he experimented with shading and color in the inkblots. Bartlett noted that subjects would typically inspect the inkblots at about an arm’s length in distance, and that when they found an image in their mind that resembled the inkblot, they would concurrently project that image into the inkblot. Bartlett noted that the most common responses were to human and animal figures and claimed that the more ambiguous inkblots were reacted to without “conscious analysis” (Bartlett, 1916, p. 37). Perhaps most notable, was the idea that the inkblots could reveal an individual’s underlying mood, or attitude towards the situation, which is related to memory recall.

1917—Cicely Parsons published a study on children’s imagination titled Children’s interpretations of inkblots. Building on the work of Dearborn, Kirkpatrick, Sharp, and Bartlett, the author used the first ten cards of the standardized Whipple series. The cards were shown five-at-a-time, in between a rest period of two weeks, due to the fatigue of the children with regards to the quality of their responses. Parsons used practice cards to prime the children for success in the association task. Most critically, Rorschach began the systematic study of human perception and learning through the Blotto game. It is reported that the doctoral work of Szymon Hens, another student of Eugen Bleuler, influenced Rorschach’s pursuit of the inkblot experiment (Ellenberger, 1954, Searls, 2017). In fact, Rorschach would cite the doctoral thesis of Hens, stating that Hens’ experiment focused on the content of responses, while Rorschach’s focused on the patterns of the perceptive process (Rorschach et al., 1942).

1918—Rorschach discovered that his inkblot technique could aid in the differential diagnosis of schizophrenia, latent or not. He innovated psychological testing by focusing on the ways that people formed perceptions from the features of his inkblots. The inspiration for the famed inkblot test stemmed from the synthesis of Jung’s word association test, Freudian free association, and Blueler’s method of navigating around conscious defenses to target genuine responses (Searls, 2017).

1921—Rorschach published a monograph on his inkblot test under the title Psychodiagnostik. However, the publisher only accepted ten inkblots due to financial concerns. These reproductions of the ten cards added new shades and chiaroscuro that brought forth “all kinds of vague forms,” (Ellenberger, 1954, p. 206). The book itself was not much of a success and sold only a few copies. And yet the influence of his experiments, and more so his ten iconic inkblots, would begin a century’s journey into global culture and science.

1922—Rorschach died from appendicitis at the tender age of 37.

1927—David Levy brought the Rorschach to America and introduced the test to his graduate student, Samuel Beck.

1936—Bruno Klopfer—who popularized the misconception of the Rorschach as an X-ray of the mind—founded the Rorschach Research Exchange (Searls, 2017).

1937—Beck’s formal method was first outlined in the 1937 monograph, Introduction to the Rorschach method: a manual of personality study.

1939-1945 (WWII period)—Lawrence Frank published his methods for projective techniques in 1939, and in the same year Bruno Klopfer founded the Rorschach Research Institute. In 1941 Harrower-Erickson and Steiner developed the Rorschach group test. 1942 was a hot streak year for the Rorschach, as the original book, Psychodiagnostik, was translated to English. David Rapaport also published his projective hypothesis, and Bruno Klopfer published The Rorschach technique. In 1943, Harrower-Erickson and Steiner published the Modification of the Rorschach method for use as a group test and Directions for administration of the Rorschach group test. In 1945 they published The Multiple Choice Test for Screening Purposes.

1945 (post WWII period)—The Rorschach test was used in the Nuremberg trials and determined that there is not a “Nazi personality,” (Searls, 2017, p. 229).

1952—Marguerite Hertz published her scoring method for the Rorschach under the title Frequency tables for scoring Rorschach responses

1953—Marked Google n gram’s peak usage of the term ‘Rorschach’ in books.

1954—Henri Ellenberger published the most-detailed account of Hermann Rorschach’s life work in the Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic. David Rapaport and Schafer publish their Rorschach scoring system under title Psychoanalytic interpretation in Rorschach testing.

1957—Piotrowski published Perceptanalysis, and by 1957 five different Rorschach scoring systems (Beck, Klopfer, Hertz, Rapaport-Schafer, & Piotrowski) were in circulation, all originating from the United States.

1961—The Holtzman Inkblot Technique is published under the title Inkblot perception and personality: Holtzman Inkblot Technique.

1969—John Exner published The Rorschach systems, a research paper on the state of the scoring systems currently in use. The paper highlighted the disparities in the various purposes and practices of each scoring system.

1974—Exner published the Rorschach: A Comprehensive System, the first of several volumes and editions on his psychometrically sound Rorschach system. The newly proposed system aimed to unite the field of practice concerning the Rorschach test.

1984—Andy Warhol painted his series of thirty-eight Rorschach inkblots.

1986—Alan Moore created the Rorschach anti hero in the 1986 graphic novel Watchmen. Meanwhile, Exner released the second edition of the Comprehensive System.

1993—Exner published the third edition of the Comprehensive System.

1996—James Wood published a critical examination of the Comprehensive System focusing on issues regarding interrater reliability, validity, and the nature of the research.

1999—Howard Garb called for a moratorium on the Rorschach in clinical and forensic settings until it was determined which Rorschach scores are valid and which ones are invalid. Wood and Lilienfeld published the Rorschach Inkblot Test: A Case of Overstatement?

2000—Gregory Meyer published a reply article (On the science of Rorschach Research) to Wood’s 1999 critique, which sparked a large back and forth between supporters and critics of the modern Rorschach for decades to come. Additionally, Lilienfeld, Wood and Garb critiqued projectives and the Rorschach in detail, but ultimately conceded that there is empirical support for the validity of a small number of indexes derived from the Rorschach and TAT. However, they concluded that the substantial majority of Rorschach and TAT indexes are not empirically supported.

2003—Exner published the fourth edition of the Comprehensive System while Wood, Garb, and Lilienfeld's book What’s wrong with the Rorschach?

2006—Charles Barkley released the music video Crazy, which featured digital inkblot art.

2009—The Film Watchmen was released, featuring the anti hero Rorschach, played by Jackie Haley.

2010—Jay Z published his book Decoded, which featured one of Andy Warhol’s Rorschach paintings on the cover.

2011—The Rorschach performance assessment system (RPAS) was published in APA by Viglione, Mihura, Meyers and other members who were on Exner's Research Council for the Comprehensive System. When Exner died, his family inherited the rights to the Comprehensive System and decided not to alter the CS. The RPAS was formed as a response to the psychometric concerns surrounding the CS, and addressed issues of validity and reliability championed by critics.

2017—Damion Searls revived the lore and utility of the Rorschach in an intriguing history of its development when he published the book The Inkblots: Hermann Rorschach, His Iconic Test, and the Power of Seeing. Also, a geometric pattern analysis study on perception revealed that Rorschach’s inkblots sit in a “sweet spot” of fractal complexity (Abbott, 2017). Too much or too little complexity led to a decrease in visual percepts, yet Rorschach’s inkblots lie within a range commonly found in nature.

After enduring a century of controversy, the Rorschach inkblot test remains an emblem of artistic creation and scientific verification. The simple question, “What might this be?” has been doing work long after its creator passed, and is still a key to deciphering the ways in which people organize and see the world. The Rorschach test’s relationship to personality is paramount, and its value is undeniable.

References

Abbott, A. (2017). Fractal secrets of Rorschach's famed ink blots revealed. Nature.

Bartlett, F.C. (1916), An experimental study of some problems of perceiving and imaging. British Journal of Psychology, 1904-1920, 8: 222-266.

Binet, A., & Henri, V. (1895). La psychologie individuelle. L’Annee psychologique, 2(1), 411–465.)

Dearborn, G. V. (1897). Blots of ink in experimental psychology. Psychological Review, 4(4), 390–391.

Dearborn, G. V. (1898). A Study of Imaginations.The American Journal of Psychology, 9(2), 183–190.

Kerner, J. (1857, 1890). Kleksographien. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt.

Kirkpatrick, E. (1900). "Individual Tests of Children." Psychological Review 7:274-280.

Leonardo da Vinci's note-books: arranged and rendered into English with introductions. (1908). Kiribati: Duckworth & Company.

Nicolas, S., Coubart, A. & Lubart, T. (2014). The program of individual psychology (1895-1896) by Alfred Binet and Victor Henri. L’Année psychologique, 114, 5-60.

Parsons, C. (1917). Children's interpretations of ink-blots. (A study in some characteristics of children's imagination). Br J Psychol.9(1):7.

Searls, D. (2017). Inkblots: Hermann Rorschach, his iconic test, and the power of seeing. Broadway Books.

Sharp, S. E. (1899). Individual Psychology: A Study in Psychological Method. The American Journal of Psychology, 10(3), 329–391.

Rorschach, H., Lemkau, P., Kronenberg, B. (1942). Psychodiagnostics : a diagnostic test based on perception, including Rorschach's paper. The application of the form interpretation test (published posthumously by Dr. Emil Oberholzer). Berne, Switzerland: H. Huber; New York: Grune & Stratton.

Whipple, G. M. (1915). Manual of mental and physical tests. Baltimore, MD: Warwick & York.

After Hermann Rorschach’s sudden death in 1922, his inkblot test began to take on a life of its own as it traveled around the world.

Recently the Rorschach test has seen another revival in media headlines.

Inkblots and dreams share plenty of common ground. They are, at once, familiar and foreign.

Be the first to know about new psychological insights that can help you optimize customer touchpoints and drive business growth.